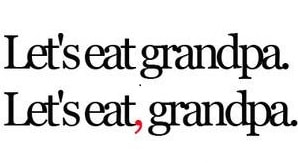

Even in this age when text is often reduced down to 140 characters or less, don’t forget the punctuation. It just could save a life! I recently went to visit my boys at their summer camp. While driving near Algonquin Provincial Park, I saw a handmade sign posted on a front lawn that read “Slow Kids Crossing.” I was so distracted by the sign (do they mean their kids are physically or mentally slow?) that I could have accidentally hit someone. It is safe to assume they intended “Slow, Kids Crossing” (or “Slow Down, Kids Crossing” would have been better), but this example goes to show the power of punctuation. The lack of punctuation in this sign obscured the intended meaning. For those of us who notice this sort of thing, it can be annoying—and sometimes amusing. Lynne Truss, author of Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation, says: “We are like the little boy in The Sixth Sense who can see dead people, except that we see can see dead punctuation.” The comma is especially complicated because it plays a grammar role, but also a role as an indicator of the rhythm and flow of the sentence. It is also the most controversial punctuation mark. People have very strong opinions about the Oxford (or serial) comma, but I will leave that heated topic for another post (there has already been enough bloodshed). The comma indicates a slight break between different parts of a sentence. The function of the comma is to group together words, phrases, and clauses to make a sentence clearer to read. The effect of a misplaced or omitted comma can be quite comical at times. Here are some examples from 25 Biggest Comma Fails on BuzzFeed:

Commas with relative clauses

A trick to make sure you have used the commas correctly is to take the information enclosed by the commas out from the sentence and see if the sentence still makes sense and conveys the meaning you intended. Commas with dependent clauses Commas with introductory words and phrases

Commas with independent clauses Commas with parenthetical and descriptive phrases

I hope you learned something from this very general introduction to using the comma. Stay tuned for a separate post in which I will discuss the use of the comma in lists.

Happy Adventures in Editing!

0 Comments

For a recent class in Advanced Writing for Health Communicators, we had to compare the websites of the Boston Ballet and the Boston Red Sox. The Boston Ballet website is sophisticated, formal, and elegant; the Red Sox website is bright, energetic, and busy. The writing and the readability of the websites are also very different indicating that they are purposefully trying to reach very different audiences. So what exactly is readability and how can you gauge the readability of your own documents? Read on to learn more. Readability and readability tests Readability is the ease with which your writing can be read. Readability tests are mathematical calculations typically based on the difficulty of the words used (i.e., the average number of syllables per word) and the difficulty of the sentences (i.e., the average sentence length). For this article, I will discuss only the ones that are freely available and built into Microsoft Word. Pros and cons of readability tests Readability tests are only predictions—they are not the definitive measure of how good your writing is. They should be used as a quick assessment during the writing/revision process. As Cheryl Stephens writes in her article All About Readability, readability tests cannot measure reader interest or enjoyment. They also cannot measure if your content is presented in a logical order, how well complex ideas are presented, or if your vocabulary is appropriate. Readability tests are best used as a screening device and they should not be the only tool you use for assessing your text. They are also good for gauging improvement in your writing if you are trying to learn how to write more clearly because they provide a quantitative number for comparison. Comparing ballet and baseball For my class, I compared the readability stats of the history page of the Boston Ballet website and the 2010s history timeline of the Red Sox website. In Microsoft Word, the readability statistics are available in the Review toolbar under Spelling and Grammar. You may need to make sure that “Check grammar with spelling” is checked under Proofing in the Options menu first. The Ballet site had more words per sentence and more characters per word than the Red Sox site (i.e., used bigger words and longer sentences). Readability testing results are listed below:

Passive sentences

The test simply finds the percentage of sentences in the document that are written in the passive voice. For writing in plain language, one of the first tips is to write in the active vs. the passive voice. In the active voice, the subject does the acting (e.g., the cat chased the dog); in the passive, the subject is acted on (e.g., the dog was chased by the cat). (I use these examples because that is the way it happens in my house.) Passive sentences flip around the sequence and natural order of the sentence and are more difficult to read. There is no strict guideline, except try to keep it as low as possible. Greater than 5% would be too high for plain writing. Surprisingly, the Red Sox site not only had more passive sentences than the Ballet site, but at 12%, it was well above an appropriate level. Not only are active sentences easier to read, they have more energy, which is exactly what they should be going for on the Red Sox site. I expected that the proportion of passive sentences would have been higher for the Ballet site—the fact that it is not shows that they had a good writer. Flesch Reading Ease The Flesch Reading Ease test rates text on a 100-point scale. The higher the score, the easier it is to understand the document. For most standard documents for a general audience, the score should be between 60 and 70. Neither the Ballet or Red Sox site made this cutoff (19.6 and 51.5, respectively), but the Ballet website was definitely low indicating that they were not even attempting to reach a “general” audience. The Red Sox site is obviously trying to reach this general audience but missed the mark. Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level test rates text on a U.S. school grade level (e.g., a score of 8.0 means that an eighth grader can understand the document). Most documents for a general audience should score between 7.0 to 8.0. Again, both websites scored outside of this ideal range for a general audience. The Red Sox site read at a grade 10 level and the Ballet site read at a senior year in university level. The Ballet site appears to be focusing on people who are university/college-educated (and who potentially have money and will buy tickets and/or donate) and the Red Sox site is geared toward those with a lower high school education. The takeaway from these tests is that both websites are trying to reach a different audience with their writing, although the Red Sox site was the less successful of the two. The Red Sox site should be geared toward a more general audience; therefore, the passive sentences should be at a minimum, the Flesch Reading Ease test score should be well about 60, and the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level needs to drop a few years. Other methods of testing readability Here are some other suggestions for testing and improving the readability of your work:

Identify your audience The most important thing you can do to make sure that you are reaching your audience is to determine who your audience is. Before you even start writing, ask yourself:

The question came up today about when to use who versus whom. Let us seek the answer from The Oatmeal. They provide far more entertaining answers to grammar questions than I could offer (I am just not that inspired by the apostrophe). Check out the links below. Do you agree? Is the semicolon the most-feared punctuation on Earth?

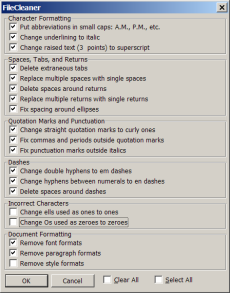

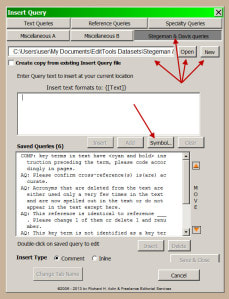

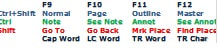

As a medical and scientific editor, I use different editing add-ins and programs for Microsoft Word that do a lot of the editing grunt work. I use these tools to clean up and prepare a paper before editing, to simplify and quicken the process while editing, and to verify that everything is consistent after editing. They are all real time savers—I never want to go back to editing on paper! I use a number of different add-ins and programs for Microsoft Word on PC. I don’t know if these are available for other word processors (are there others?) or if they are also available for Mac. Note that I am using Word 2010 and that these may not be available for earlier versions of Word. I have included current prices for them, but many do offer a free trial. Here is a list of the ones I use in the typical order that I use them.  Before Editing FileCleaner for Microsoft Word by The Editorium (US $29.95) Some papers arrive as a bit of a visual mess with multiple fonts and font sizes, weird spacing, and unusual punctuation styles. With these papers, it’s hard to see the forest for the trees. Before I even start editing a paper (except those preformatted by the journal), I clean it up with FileCleaner. I use it to strip all of the formatting, get rid of all of those pesky double spaces after periods, and any multiple returns or unnecessary tabs. It can also automatically put punctuation within quotation marks, change hyphens between numbers to en dashes, and even change a capital O used as number to zero. It can do this for a single active document, all open documents, or even a whole directory at one time. After running FileCleaner, I can change the paper to a consistent font and a comfortable font size and it is ready for editing. FRedit by Paul Beverley (Free!) This one is a bit more complex to use because it uses macros (an alien language to me), but it is very powerful once you get the hang of it. FRedit is a scripted global find-and-replace macro. You write in a Word file a list of words to find with their replacements. FRedit then uses this script to search an open document for these words and then replaces them with the words that you indicated (don’t forget to turn on Track Changes beforehand!). This is a very simplified description of what it can do. The power is that you can have multiple scripts with multiple find and replaces within each script. For example, one script that I use for an American journal changes spelling from UK to US (and I can keep adding words to the list), changes numbers to numerals, removes hyphens from prefixes (as per AMA style), changes certain words to preferred spellings, and italicizes statistical terms, such as P, F, r, and d. I have another script that I run without Track Changes on that highlights tricky words and phrases that are commonly misused. I don’t even scratch the surface of what FRedit is capable of doing, but it already saves me so much time. Paul has always been helpful when I have had questions or problems. He also has a free 600-page book, Macros for Writers and Editors. And you can’t beat the price (he does suggest a £10 donation to charity)!  During Editing EditTools by wordsnSync (US $69.00) This add-in has many functions, but what I use it for is its Insert Query function. Like you, I have standard queries or comments that I use all the time. With Insert Query, I don’t have to write these out over and over again. I can insert them with just a click of a button. The Insert Query function allows me to organize the queries by journal or topic (e.g., “statistics queries”). Under each of these tabs, I have saved the queries that I use most often or ones that are quite lengthy. The queries can be inserted inline or as a comment, whatever you prefer. EditTools offers many more functions (Wildcard Find and Replace, Language Conversion, Page Number Format, etc.), but I do not use them so I cannot comment on them. The Insert Query function alone is worth the price for me. Stedman’s Medical/Pharmaceutical Spellchecker by Wolters Kluwer Health (US $99.95) Stedman’s Medical Dictionary is a must for any medical writer or editor. The Stedman’s Spellchecker is a software program that integrates with the existing spellchecker within Word to automatically spellcheck all medical words. Do you really want to look up words like myringostapediopexy every time? Stedman’s Spellchecker runs automatically (you don’t have to run a separate application) and it contains nearly 500,000 medical, pharmaceutical, and bioscience terms as well as medical equipment, surgical procedures, diagnostic tests. The new 2014 version includes a universal spellchecker that will spellcheck across your entire desktop. The software comes on CD-ROM that you install onto your computer.  Editor’s ToolKit by The Editorium (US $29.95) Editor’s ToolKit includes a lot of macros with many of the most frequently accessed functions assigned to the function keys on the keyboard. By hitting a F1–F12 key with or without shift, control, or control+shift, I now have 48 tools easily accessible through my function keys. They provide a template that you can print out, which I laminated (of course!) and taped onto my keyboard above the function keys so I can reference it easily. I use these all the time. The F9 key will cap all selected words; F10 makes them lowercase. And you have 46 other functions, including open, close, small caps, insert em dash, and so on. Many people write their own macros for many of these, but what I like about this is that they are all assigned to the function keys (I am guaranteed to forget a macro 5 minutes later) and the template is an easy reminder that does not take up a lot of real estate on your desk. You can purchase Editor’s ToolKit Plus which also includes FileCleaner (and QuarkConverter and NoteStripper) for US $69.95—a savings of $50.00 if you bought all separately.  Tabs for Word by ExtendOffice (US $15.00) This add-in is not specifically for editing, but it is extremely useful. It adds a tab bar to Word that displays all open documents so that you can quickly jump back and forth between the journal article you are editing and the journal style guide all within a single window without having to close and open different windows. A simple but handy tool.  After Editing PerfectIt by Intelligent Editing (US $59.00) There are different ways to use PerfectIt. I know some editors like to use it before editing as a sort of first pass. Personally, I use it as the very last step in the copy editing process. The copy editor’s mantra is consistency, consistency, consistency. PerfectIt is genius because it finds inconsistent spelling, hyphenation, and capitalization throughout the paper. It has many other functions, including generating a table of abbreviations that are used within the paper. After a final edit, it can also search for comments or edits that have accidentally been left in the paper. And it is completely customizable. I have different style sheets for every journal as well as other general ones for Canadian or American spelling. There you have it—my little army working behind the scenes. Could you just run these programs and add-ins and hand the paper back to your author? Absolutely not! These tools can make your job easier, not make it disappear altogether. A computer program can’t replace a good editor because the computer can never understand the author’s intention or meaning. My job is safe for another day. Is there an add-in or program that you use while editing that you can’t live without? Let us know about it. Happy Adventures in Editing! “If you can‘t explain it simply, you don‘t understand it well enough.” -Albert Einstein I edit so many research papers in which the writers take the most convoluted and circuitous routes to get a simple point across. Instead of being impressive and scholarly, it is just confusing. Your writing is more effective—and your reader can actually understand it—when you use plain language. The “Dizzy Awards” have been given out by the Texas Heart Institute Journal for the past 30 years for excellence in “unintentionally comical, bewildering, or downright terrible” medical writing (they don’t name names). Check out this gem that was published in a prominent medical journal: “The development of Goodpasture’s disease may be considered an autoimmune ‘conformeropathy’ that involves perturbation of the quaternary structure of the A345NC1 hexamer, inducing a pathogenic conformational change in the A3NC1 and a5NC1 subunits, which in turn elicits an autoimmune response.” (2012 Dizzy Award Winner) If the reader has to re-read each paragraph multiple times to understand your point, you have lost them. Writing in plain language is not a “dumbing down” of your work—it is ensuring that your reader will understand it the first time that they read it. Writing in plain language is a lot harder than it sounds. You may have heard this quote: “If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter.” It is actually quite difficult to write in plain language. But I am here to give you some tips and tricks! Use short sentences A general rule of thumb is to keep your sentences to an average of 20 words or fewer with one idea per sentence. This is especially true for the lead sentence in a paragraph. If your sentences are running multiple lines with many commas and/or semicolons, break them up into smaller sentences. Longer sentences are not forbidden—just try to keep most short for easier reading. Below is an example of the type of sentences I see all the time (shiver!). This one should have been a short sentence and a concise table: “The greater pain caused by larger-size tubes was the result of increased pain during the insertion of the tube and pain while the tube was in situ, with no pain difference during tube removal (insertion: size < 10F, MPS 2 [IQR 1–2]; size 10–14F, MPS 2 [IQR 1–3]; size 15–20F, MPS 2 [IQR 1–3]; size > 20F, MPS 2 [IQR 2–3]; χ2, 3 df = 8.12, P = .044, Kruskal-Wallis; χ2 trend, 1 df = 7.2, P =.009. in situ: size < 10F, MPS 2 [IQR 1–3]; size 10–14F, MPS 2 [IQR 1–2]; size 15–20F, MPS 2 [IQR 2–3]; size > 20F, MPS 2 [IQR 2–3]; χ2, 3 df = 11.75, P = .008, Kruskal-Wallis; χ2 trend, 1 df = 6.2, P = .015. removal: size < 10F, MPS 2 [IQR 1–2]; size 10–14F, MPS 1 [IQR 1–2]; size 15–20F, MPS 2 [IQR 1–2]; size > 20F, MPS 1 [IQR 1–2]; χ2, 3 df = 2.7, P= .44, Kruskal-Wallis; χ2 trend, 1 df = 1.0, P = .31 (Fig 2).” (2010 Dizzy Award Winner) Use the active versus the passive voice In the active voice, the subject does the acting; in the passive voice, the subject is acted on. For example, “constipation is reported in over 33 million adults…” (2009 Dizzy Award Winner) should be “33 million adults reported constipation…” (and reports can’t appear in patients!). Use common, everyday words Basically, use the simplest word for the job. For example, use “use” versus “utilize.” Technical terms are fine, but be aware that your reading audience may come from different research areas or other countries that use different technical terms. Rule number two in George Orwell’s Six Rules for Writers is “never use a long word where a short one will do” and number five is “never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.” Listen to George, he knows what he is talking about. Define all of your abbreviations or acronyms on first use Sure, it may be a common abbreviation used by everyone in your nuclear physics lab, but be aware that people from outside your lab or from other countries may use different ones. People from other specialties may use the same acronym for an entirely different term. In medicine, “CA” is the abbreviation for cancer, cardiac arrest, chronologic age, contrast angiography, and others. Avoid confusion and define your terms. And remember to define on first use in both the abstract and the body of the paper. Avoid using abbreviations or acronyms for convenience Many authors will devise their own sets of abbreviations or acronyms for use in a single paper. These ones are not in common use and are devised by the author so that they do not have to write certain phrases over and over again (lazy!). For clarity, keep the terms expanded. The exception to this is in tables where space is at a premium. Even then, the abbreviation(s) should be clearly defined in the caption or in a footnote. For example, in “Because it is both a common and serious condition, elderly nursing home (NH) residents are…” (2010 Dizzy Award Winner), nursing home should be left expanded—and being a resident is not a common and serious condition to top it off. Write in the positive versus the negative Each negative term used obscures the clarity of your message exponentially. Look at these examples:

Avoid redundant and ambiguous words Phrases such as fewer in number, future plans, and sum total are all redundant (i.e., both words mean the same thing). An example of redundancy is the “one solitary” used in this sentence (and is there an Alcoholic Skeletal Myopathy Journal for this to be described in?): “Except for one solitary case, acute cardiac dysfunction has not been described previously in alcoholic skeletal myopathy.” (2010 Dizzy Award Winner) Finally, your spellchecker is your friend. Don’t forget to use it. There are also a number of other programs and macros that can be used to spot and correct problems, but that is another adventure.

Happy adventures in editing! 1. Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech that you are used to seeing in print.

2. Never use a long word where a short one will do. 3. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out. 4. Never use the passive where you can use the active. 5. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent. 6. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous. Politics and the English Language (1946) |

AuthorI am freelance copy editor, proofreader, and instructor based in Toronto. Enjoy my adventures in editing! (Note: I transferred my blog over and lost my comments along the way, unfortunately. Please add new ones.) Archives

October 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed