©Kristine Thornley ©Kristine Thornley Copy editing medical content requires a basic knowledge of medical terminology or the “language of medicine.” It is the medical copy editor’s job to ensure that the right terms are used and that they are spelled correctly. There is a big difference between a colonoscopy and a colostomy—and you do not want to be the one to mix them up. You will be a more effective and efficient medical copy editor with a good foundation in medical terminology.  Body’s Systems and Basic Physiology Understanding medical terminology starts with knowing the body’s systems and the parts that comprise them (skeletal, muscular, integumentary, cardiovascular, lymphatic, respiratory, gastrointestinal, endocrine, nervous, urinary, and reproductive) as well as some basic physiology. If you do not have a biology background, the Khan Academy offers free online courses in human anatomy and physiology. InnerBody is a free virtual human anatomy website that offers hundreds of interactive anatomy pictures and system descriptions. Or perhaps you would like to take a “peek under the hood” with Anatomy & Physiology For Dummies.  Common Medical Terms and Medical Root Words You need to be familiar with common medical terms and medical root words. Most common medical terms used today are derived from Latin or Greek, which makes sense since the Greeks were the founders of modern medicine. Having some knowledge of the Latin and Greek bases of words will go a long way to understanding the word and ensuring that it is used correctly. For example, the Greek roots myo (muscle) and myelo (bone marrow) look similar but have very different meanings. I was fortunate to take a “Latin and Greek for Scientists” course in undergrad, but I suspect that many of you with a natural love for language will already have some knowledge in this area. As a starting point, here is a list of medical roots, suffixes, and prefixes with their meanings and etymology. For medical terms, the Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy is the most widely used comprehensive medical textbook for both professionals and consumers (available in print, online, and as an app). The American Medical Writers Association also offers a self-study workbook on Elements of Medical Terminology that is designed primarily for those with little or no medical background. You do not have to be a member to purchase it.  Correct Spelling and Common Errors The field of medicine is filled with ridiculously complicated terms, such as sphenopalatine ganglioneuralgia (“ice cream headache”) and unusual spellings (eg, hemorrhoid, diphtheria). You are definitely going to need a medical dictionary. Stedman’s Medical Dictionary is the authoritative spelling resource for more than 54,000 medical terms and it is available in print, online, and as an app. Stedman’s also offers a medical/pharmaceutical spellchecker that is compatible with many word processing systems. Windows users also receive a universal spellchecker that integrates medical and pharmaceutical spellchecking throughout the entire desktop, not just in Word. This is an invaluable tool for medical copy editors. I will discuss abbreviations and word usage in medical writing in future posts. Until then, happy adventures in editing!

1 Comment

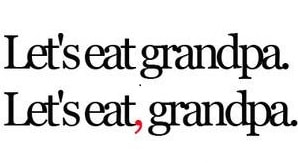

“If publishing were like getting dressed in the morning, the copyeditor would review the chosen outfit, bearing in mind the weather and what the day’s agenda entails. She may decide on different shoes or a wider belt. She may pick out a different jacket. She may even suggest an entire wardrobe change. She examines the overall appearance and makes suggestions to create the nicest-looking ensemble that ever stood in front of the bedroom mirror. The proofreader then waltzes in and points out the deodorant marks on the shirt.” (Suzanne Gilad, Copyediting & Proofreading for Dummies) Many authors who contact me think that proofreading is synonymous with copy editing (and sometimes copy editing is synonymous with copy writing, but that’s a different story). But copy editing and proofreading are two different processes done at two different stages of production. When I explain to an author who is clearly looking for copy editing that proofreading is actually the final step after typesetting and layout, I still have many who say that is what they need because they have already put their manuscript in final publishing format—without having copy edited the text first. Editors can understand how eager authors are to see their manuscript “look” like a book, but there are stages that should be followed so that you do not end up wasting valuable time and money. According to the Professional Editorial Standards of Editors Canada, copy editing is defined as “editing to ensure correctness, accuracy, consistency, and completeness,” whereas proofreading is “examining material after layout or in its final format to correct errors in textual and visual elements.” Science or Art? Regarding the text, it has been said that proofreading is a science, editing is an art. Proofreading is correcting text. Copy editing is not just correcting, it is also improving. Let’s take a look at the following example:

Notice the difference. In the proofread correction, the text remained the same, but the spelling and number errors were fixed. In the copy edited correction, the wordiness of the sentence was corrected. This change in wording makes it a “stronger” sentence. The proofreader would not change the wording. As long as it is understandable, the proofreader would leave it as it is and fix the copy editing and layout errors only. When, Where, and How Copy editing and proofreading differ in when, where, and how they are done. The copy editor works on the manuscript before layout, usually on-screen in a Word document. This is a much easier time and location to copy edit. The copy editor can adjust the font size and line spacing of the document for easier reading without worrying about messing up the layout. The copy editor also has access to lots of built-in Word functions as well as add-in Word tools and macros to help in the process. The proofreader, on the other hand, works on proofs of the final manuscript after layout, usually within a PDF or on a hard copy (printed out version). Space to work is far more limited in this format and the proofreader reviews things that the copy editor never sees, such as all the style and visual elements, cross-references and running heads, typography and page formatting. Copy editing (manuscript in a Word document) Proofreading (PDF proof of page spread) How are corrections marked? When copy editing a Word document, track changes is used to mark errors and changes to the text. Errors and text changes are marked directly within the body of the text. Comments are usually made within the margins. In proofreading, however, changes have to be indicated in two places: within the body of the text using standard symbols and a corresponding symbol or note/query in the margin on the same line so that the error can be easily spotted. A summary of the differences is presented below:

What other differences are there between copy editing and proofreading? Share them with us.

Happy Adventures in Editing!  Even in this age when text is often reduced down to 140 characters or less, don’t forget the punctuation. It just could save a life! I recently went to visit my boys at their summer camp. While driving near Algonquin Provincial Park, I saw a handmade sign posted on a front lawn that read “Slow Kids Crossing.” I was so distracted by the sign (do they mean their kids are physically or mentally slow?) that I could have accidentally hit someone. It is safe to assume they intended “Slow, Kids Crossing” (or “Slow Down, Kids Crossing” would have been better), but this example goes to show the power of punctuation. The lack of punctuation in this sign obscured the intended meaning. For those of us who notice this sort of thing, it can be annoying—and sometimes amusing. Lynne Truss, author of Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation, says: “We are like the little boy in The Sixth Sense who can see dead people, except that we see can see dead punctuation.” The comma is especially complicated because it plays a grammar role, but also a role as an indicator of the rhythm and flow of the sentence. It is also the most controversial punctuation mark. People have very strong opinions about the Oxford (or serial) comma, but I will leave that heated topic for another post (there has already been enough bloodshed). The comma indicates a slight break between different parts of a sentence. The function of the comma is to group together words, phrases, and clauses to make a sentence clearer to read. The effect of a misplaced or omitted comma can be quite comical at times. Here are some examples from 25 Biggest Comma Fails on BuzzFeed:

Commas with relative clauses

A trick to make sure you have used the commas correctly is to take the information enclosed by the commas out from the sentence and see if the sentence still makes sense and conveys the meaning you intended. Commas with dependent clauses Commas with introductory words and phrases

Commas with independent clauses Commas with parenthetical and descriptive phrases

I hope you learned something from this very general introduction to using the comma. Stay tuned for a separate post in which I will discuss the use of the comma in lists.

Happy Adventures in Editing!  Image from CartoonStock.com (used with permission) Image from CartoonStock.com (used with permission) In my last post, I discussed the results of a recent study that found our sedentary editing and writing jobs increase our risk for some cancers. In part two, I offer some tips that may just save your life (I like to think so anyway). Move during the day “Sitting is the new smoking,” says Brigid Dineen, Life Coach, yoga instructor, and organizer for the Yogapalooza festival in Toronto. “Although you can’t quit sitting, you can take action to minimize its consequences on your health and well-being.” Brigid suggests we take a break and get moving at least once an hour. “It will help to improve your posture, your circulation, your stress levels and mood, and your mental focus. You will also reduce your risk of back pain, weight gain and becoming a ‘zombie’ from staring at the screen for too long.” Any activity will do. Take a walk, do some stretches, or—Brigid’s favorite—take a dance break! Be intentional about taking a break or the day will get away from you (even set a timer to remind you). Here are some great options:

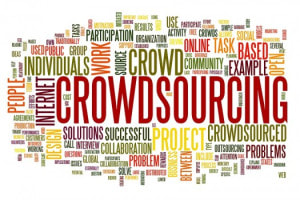

Get your vitamin D Vitamin D deficiency may be the biological pathway through which excessive sitting increases cancer risk. If you can’t get outside during the day for a walk to catch some natural vitamin D, take a supplement. Be more active outside work hours Sitting risk is cumulative. If you work at a desk all day and spend your evenings sitting on the couch watching TV, you are in real trouble. Spend your leisure time being more active. Take a walk. Take up a sport. Learn ballroom dancing. Just get moving! For your workspace Some people like to use a standing desk or sit on an exercise ball while working. Even just placing your garbage can or printer on the other side of the room will help because you will have to get up to use them during the day. Tell us, what do you do to break up your sitting time during the day?  I never considered editing a dangerous job. In fact, editing fulfilled all my safe job criteria: it involved a lot of sitting and could be done in my pajamas. The only danger was an occasional coffee spill. New research finds sedentary desk jobs, such as writing or editing, can increase our risk for cancer—and even exercising every day does not reduce this risk. Sitting is the new smoking Excessive sitting has already been found to increase our risk of obesity as well as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension and even depression. According to a recent meta-analysis of 43 observational studies that included over 4 million individuals and 68,936 cancer cases, increased sitting time each day also increases our chance of colon, endometrial and lung cancers. In addition, each two-hour per day increase in sedentary time was related to a statistically significant 8% and 10% increase in colon cancer and endometrial cancer risk, respectively (a 6% increased risk of lung cancer was borderline significant). Several mechanisms were suggested including increased weight gain and obesity, vitamin D deficiency, and inflammatory responses triggered within the body. All sitting is not created equal Sitting watching TV was found to more detrimental than occupational sitting. Another prospective study reported that each two-hour per day increase in TV time was associated with a 23% increased risk of obesity, but only a 5% increased obesity risk for sitting at work time. The authors suggest that this is because we are more likely to snack on unhealthy food while watching TV. Exercise isn’t enough Perhaps even more concerning was that adjusting for exercise did not affect the positive association between sedentary behavior and cancer in this most recent study. This means that the increased cancer risk is not just due to inactivity and that exercising after sitting all day isn’t enough to counteract this risk. It is like thinking that going for a jog will make up for smoking a pack of cigarettes a day. But wait—you don’t need to change careers! Read part two to find ways to lessen your risk. “Too many cooks spoil the broth” –English proverb  Today’s adventure in editing was an “offer” I had not seen since I first started out in editing. An author wanted me to edit a chapter of his book—for free (“it was only one chapter”). Presumably as many editors as he had chapters in his book were also contacted with this deal. His goal was to end up with an edited book for nothing. Almost every editor has been approached with this scam at some point during their career. Sometimes we are offered a pittance; sometimes we are promised “great exposure.” “Next time I go grocery shopping,” said fellow editor Katherine Barber, “I’m going to say, ‘Hey Loblaws, give me my groceries for nothing and I’ll tell all my friends on Facebook and Twitter how wonderful you are.’ ” You wouldn’t do it with your grocery store—it is just as inappropriate when dealing with a professional editor. It is usually an inexperienced author who tries this, one who does not understand the role or the value of an editor. One of the primary goals of editing is consistency, consistency, consistency. How do you achieve this with a dozen different editors? Yes, editing can be expensive (it is a professional service after all). If you truly think you have “probably the greatest story ever written” (actual quote), don’t shortchange your work by farming it out in small chunks to many different editors in an effort to save money. You might actually have the greatest story idea ever, but if you are an inexperienced writer it takes a lot of work—by you and your editor—to get it to greatest story level. How can you afford an editor? You are creative—think creatively! But be sure to discuss your proposal with your editor before editing begins. After you receive the invoice is not the time to propose your idea. Here are some suggestions to get you started (with many thanks to the members of the Editors’ Association of Earth Facebook group for their wonderful recommendations and anecdotes). Barter Everyone has something to offer and many editors are open to bartering. The EAE editors have received bottles of wine (what wouldn’t I do for some bottles of wine?), pieces of art, laundry or grocery delivery, meals, or services such as house painting or installing carpet. Remember that bartering is still counted as income and subject to tax (editors will have to issue a receipt with an equivalent dollar amount and submit at tax time). Crowdfund Crowdsourcing is splitting a large task up into very small projects that are completed by many different people. Instead of splitting up the job into pieces, split the cost of hiring a good editor. Crowdfunding is raising money through small contributions from a large number of people via the Internet and social media. Pubslush is a crowdfunding platform specifically for authors, but there are many other crowdfunding sites, such as Indiegogo and Kickstarter. You could offer contributors a signed copy of your book once published, a chance to name a character, or an acknowledgement within the book. Hire a recent grad It is very difficult for a new editor just starting out to establish themselves and generate clients. A recent grad from a publishing program may be willing to do the project for less money to build their project list. They should have formal editing training. You want them to have the skills—they just may not be as quick as a more experienced editor. The Publishing program at Ryerson University in Toronto (where I studied publishing) offers a job announcement service for grads. You can contact them with the details of your project and they will distribute your job posting to current students and alumni free of charge. Check your local universities for a similar service if you live outside the Toronto area. Do the work yourself Maybe hiring an editor is completely out of the question for you financially. There are many books out there that can teach you the basics. It just takes an investment of your time—and a library card. The bonus is that you now will have these self-editing skills for your next project. Here are some of my favourites:

Get a little help from your friends Have as many people as possible—your spouse, friends, relatives, the guy down the street—read your manuscript and provide feedback. This is a good start, but know that because these people have a relationship with you, their feedback is going to be censored somewhat. As famous editor Alan D. Williams has said, “An editor [does] something that almost no friend, relative, or even spouse is qualified or willing to do, namely to read every line with care, to comment in detail with absolute candor, and to suggest changes where they seem desirable, or even essential. In doing this the editor is acting as the first truly disinterested reader, giving the author not only constructive help but also, one hopes, the first inkling of how reviewers, readers, and the marketplace…will react, so that the author can revise accordingly.” You do need unbiased eyes to assess your work, so another option is to join a writers’ group or writing circle. They are all writers and committed to writing. Their input could be invaluable. But it is not a one-way street. You will be expected to help with other writers’ works too. Check your local library for a group that meets face-to-face or check the Web for online writing groups, such as Scribophile. Share some of your creative ideas or your past experiences. Happy Adventures in Editing! P.S. Make sure to visit Katherine’s Wordlady blog too—it is wonderful. The question came up today about when to use who versus whom. Let us seek the answer from The Oatmeal. They provide far more entertaining answers to grammar questions than I could offer (I am just not that inspired by the apostrophe). Check out the links below. Do you agree? Is the semicolon the most-feared punctuation on Earth?

ed∙i∙tor \e-də-tər\ n (1649) 1. A person who prepares literary material for publication or public presentation Editing is both a science and an art. It is a combination of training, experience, and natural ability. You should be comfortable with your editor and confident in her decisions. The following are characteristics that all good editors should have (and qualities I think I can bring to your project):

1. Broad knowledge base A good editor has both wide-ranging and specialized knowledge to be able to pick up factual errors. She has to be a bit of a Renaissance person (or polymath)—and she is usually a really good Trivial Pursuit or QuizUp player. 2. Meticulous A good editor has an almost infinite capacity for detail. She requires a great sense of quality and possesses high standards of accuracy. She questions everything and applies a critical eye to the tiniest detail in order to recognize patterns and locate inconsistencies. You could use the word obsessive, but I prefer meticulous. 3. Loves language Not only must a good editor love the written word, but she must also have flawless knowledge of grammar and style. Or at least be able to look it up if she is not sure. She is often a bit of a grammar guerilla: tiny mistakes in the newspaper seem to immediately jump off the page. She has an appreciation for the Oxford comma and knows that despite what we were taught in school, it is not a mortal sin to leave a participle dangling. She also knows that when the right words are put together properly, they can be as beautiful as a work of art. 4. Diplomatic Telling an author that there is a major problem with the manuscript that they have devoted months or years of their life to creating is like telling a mother that her child is funny looking. Tact is vital. So is humility. A good editor acts as a coach to her writers. She is able to be encouraging while still pointing out the areas that need correction. 5. Able to meet deadlines Publishing is rife with deadlines. If you are late in one stage of the process, it causes a chain reaction everywhere else down the line. A good editor has to be able to estimate timelines and meet deadlines. She also needs to be flexible because there will be an inevitable bump in the road with almost every project. Don’t forget to check out my website. Happy Adventures in Editing! |

AuthorI am freelance copy editor, proofreader, and instructor based in Toronto. Enjoy my adventures in editing! (Note: I transferred my blog over and lost my comments along the way, unfortunately. Please add new ones.) Archives

October 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed